The Headhunting in Borneo: A Bloody History and Spiritual Quest

Deep within the emerald embrace of the Southeast Asian rainforests, where the mist clings to the canopy like a shroud, lies a history that is as captivating as it is terrifying. It is a tale of spiritual power, tribal warfare, and a tradition that has fascinated and frightened the Western world for centuries. We are speaking, of course, of headhunting in Borneo.

For the modern traveler from the United States, Singapore, or Australia, Borneo evokes images of orangutans, diving in Sipadan, and lush biodiversity. However, beneath this eco-tourism paradise lies the legacy of the Borneo headhunters—warriors who once patrolled these jungles, seeking not just victory, but the spiritual essence trapped within the human skull.

This article delves deep into the bloody yet culturally complex history of headhunting in Borneo, separating colonial myth from tribal reality, and exploring how this ancient practice shaped the identity of the Dayak people.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Who were the headhunter tribes in Borneo?

While the practice was widespread across the island, the most well-known Borneo headhunters were the Iban (Sea Dayaks) of Sarawak, the Murut of Sabah, and the Kayan and Kenyah tribes of the interior. The Iban were famous for their expansionist river raids, while the Murut were feared for their requirement of a head for marriage eligibility. Each tribe had its own specific rituals and spiritual justifications for the practice.

2. What is the history of headhunting?

The history of headhunting in Borneo spans centuries. Originally, it was a spiritual obligation used to end mourning periods, ensure fertility, and prove manhood. In the 19th century, the “White Rajahs” (the Brooke family) and colonial powers worked to ban the practice through forts and peace-making ceremonies. It largely ceased by the early 20th century but saw a brief, terrifying revival during World War II, encouraged by Allied forces to combat Japanese occupiers. Today, it is strictly a historical narrative.

3. What is a mandau sword?

The mandau sword is the traditional weapon of the Dayak people, specifically associated with the Kayan and Kenyah, though widely recognized across Borneo. It is a single-edged blade characterized by a unique convex and concave profile, designed for powerful slicing cuts. Beyond its use in warfare, the mandau sword is a spiritual object, often adorned with human hair and intricate carvings, believed to possess supernatural powers. It is distinct from the parang ilang, which is the specific war sword of the Iban people.

4. What is the Z Special Unit in Borneo?

The Z Special Unit was an elite Allied special forces command during World War II, comprised mainly of Australian and British operatives. They parachuted into the jungles of Borneo to organize local resistance against the Japanese occupation. The Z Special Unit is famous for forming a close bond with the indigenous Dayak tribes, effectively “reactivating” the headhunting tradition as a form of psychological and guerilla warfare against Japanese troops.

5. Are there still headhunters in Borneo?

No, the active practice of headhunting in Borneo has been extinct for decades. Modern laws, religious conversion (to Christianity and Islam), and development have ended tribal warfare. However, the descendants of the Borneo headhunters keep the culture alive through dance, festivals, and the preservation of ancestral skulls in longhouses. It is perfectly safe for tourists to visit these communities today.

Beyond the Savage: Understanding the "Why"

To view headhunting in Borneo simply as an act of savagery is to misunderstand the fundamental spiritual beliefs of the Dayak people (the collective name for the indigenous tribes of Borneo, including the Iban, Kayan, Kenyah, and Murut). It was not merely about violence; it was about survival, prosperity, and the accumulation of semangat (soul substance).

The Cult of the Skull

The indigenous tribes believed that the head was the repository of the spirit. By taking a head, a warrior did not just kill an enemy; he captured that person’s power and brought it back to his own village. This act of headhunting in Borneo was believed to ensure a bountiful rice harvest, protect the longhouse from evil spirits, and ensure the fertility of the tribe’s women.

Without the influx of new spiritual power through fresh heads, the community feared their crops would fail and their lineage would wither. Thus, headhunting in Borneo was less about hate and more about a desperate metaphysical need to keep the cosmic balance in favor of one’s own community.

The Rite of Passage

For a young man growing up in a longhouse, headhunting in Borneo was the ultimate test of manhood. A man could not hope to marry the most desirable woman in the village unless he had proven his bravery. Returning with a head was the undeniable proof of his prowess. It signaled to the tribe that he was a protector, a provider, and a warrior capable of defending the community against rival Borneo headhunters.

The Tribes of Terror: Who Were They?

While many tribes inhabited the island, a few were particularly renowned (and feared) for their dedication to the practice.

The Iban (Sea Dayaks)

Perhaps the most famous of the Borneo headhunters, the Iban of Sarawak were maritime warriors who expanded aggressively along the river systems. Their expansionist nature meant that headhunting in Borneo was often a byproduct of territorial conquest. They were fearless, navigating the rivers in war boats, driven by the desire for land and the spiritual necessity of heads to bless their migration.

The Murut and Kadazan-Dusun

In the northern region of Sabah, the Murut were arguably the most feared. It was said that a Murut man could not marry until he had taken a head. Similarly, the Kadazan-Dusun had their own distinct rituals. The famous warrior Monsopiad, a legendary figure in Sabah, is a prime example of the individual glory associated with headhunting in Borneo. His house of skulls remains a tourist site today, a stark reminder of the past.

The Tools of the Trade: Artistry in Death

One cannot discuss the history of headhunting in Borneo without examining the exquisite, deadly weaponry that made it possible. These were not blunt instruments; they were forged with high-carbon steel and imbued with spiritual significance.

The Mandau Sword

The primary weapon of the Dayak warrior was the mandau sword. This was not just a machete; it was a status symbol. The mandau sword is distinct for its single-edge blade, which is convex on one side and concave on the other. This unique design allowed for incredibly deep, slicing cuts—perfect for the grim task of decapitation.

The hilt of a high-quality mandau sword was often carved from deer antler, featuring intricate designs of dragons or spirits, adorned with tufts of animal hair. A warrior believed that his mandau sword had a spirit of its own. It had to be treated with respect, fed with blood during rituals, and never unsheathed without cause. To hold a mandau sword is to hold a piece of history that commands immediate reverence.

The Parang Ilang

While often used interchangeably with the Mandau in casual conversation, the parang ilang is specifically the Iban designation for their war sword. The parang ilang shares similar characteristics with the Mandau, particularly the complex grinding of the blade. Using a parang ilang required immense skill; because of the asymmetrical grind, an inexperienced user would find the blade glancing off the target.

The parang ilang was worn at the hip, suspended by a braided rattan belt. Attached to the sheath was often a smaller knife (used for cleaning the primary blade or small tasks) and a pouch for magical charms. When the Iban conducted raids, the flash of the parang ilang was often the last thing an enemy saw. Today, antique collectors covet the parang ilang for its metallurgical mastery and connection to the age of headhunting in Borneo.

The Ritual: Preservation and Celebration

Once a raid was successful, the practice of headhunting in Borneo shifted from warfare to ceremony. The return of the war party was met with jubilation.

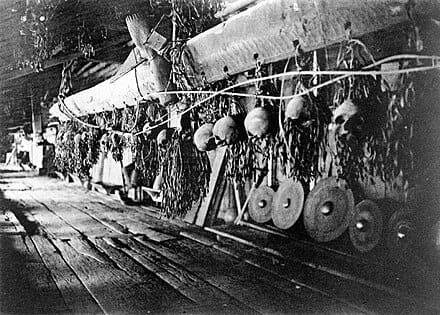

The heads were not simply tossed into a pile. They were treated with a mix of mockery and respect. The flesh was removed, often by boiling or leaving the head in a river basket for aquatic life to clean. The skull was then smoked over a hearth fire. This smoking process, central to the ritual of headhunting in Borneo, preserved the skull and gave it a darkened, aged appearance.

During the Gawai Kenyalang (Hornbill Festival) or specifically the Gawai Antu (Festival of the Spirits), these skulls were taken down from the rafters. They were “fed” with tuak (rice wine) and offerings of food. The logic was simple: if the spirits of the enemies were treated well, they would serve the community as guardians rather than vengeful ghosts. This duality—killing the man but honoring the spirit—is what makes headhunting in Borneo such a unique anthropological study.

The White Rajahs and the Suppression

In the 19th century, the narrative of headhunting in Borneo took a sharp turn with the arrival of James Brooke, the first White Rajah of Sarawak. Brooke and his successors sought to suppress the practice, viewing it as barbaric and a hindrance to trade.

Through a combination of military force and diplomacy, the Brookes began to outlaw headhunting in Borneo. They built forts along the rivers to monitor the movement of the Iban and penalized tribes that continued the practice. Slowly, the taking of heads began to decline. The mandau sword was used more for clearing jungle paths than for severing necks, and the parang ilang became a ceremonial object rather than a tool of war.

By the 1930s, it seemed that headhunting in Borneo had been relegated to the history books, a story told by elders to frighten children. But history has a way of repeating itself, and the most famous resurgence was yet to come.

World War II: The Return of the Headhunters

The Japanese occupation of Borneo during World War II brought immense suffering to the local population. It also triggered a revival of headhunting in Borneo that terrified the occupying forces.

The Role of the Z Special Unit

This revival was catalyzed by the Z Special Unit, a joint Allied special forces command (largely Australian and British). The Z Special Unit parachuted into the dense jungles of Borneo to organize a guerilla resistance against the Japanese. These commandos, realizing the fierce potential of the Dayak people, formed bonds with the tribes.

The Z Special Unit encouraged the Dayaks to resume their old ways to strike fear into the Japanese ranks. For the indigenous warriors, this was a release of pent-up cultural energy. The ban was lifted. The parang ilang was sharpened once more. The Z Special Unit provided modern firearms, but for close-quarter jungle ambushes, the Dayaks preferred their traditional blades.

A Psychological Weapon

Reports from the era describe Japanese patrols venturing into the jungle and never returning, or their headless bodies being found days later. The psychological impact was devastating. The Japanese feared the silent blow of the mandau sword more than the crack of a rifle. The Z Special Unit successfully leveraged the ancestral skills of the Borneo headhunters to turn the tide of the war in the interior.

This unique collaboration between the Z Special Unit and the Dayaks is one of the most fascinating chapters in military history. It legitimized headhunting in Borneo one last time, transforming it from a “barbaric act” into a heroic defense of the homeland. The skulls taken during this period were often hung in the longhouses alongside those from centuries prior.

The Mandau and Parang Ilang in Combat

To understand the lethality of these encounters, one must appreciate the engineering of the weapons used alongside the Z Special Unit.

The mandau sword is designed for a specific range of motion. Unlike a katana which slices, or a broadsword which hacks, the mandau sword functions with a whip-like chop. In the dense undergrowth of Borneo, where swinging a long weapon is difficult, the mandau sword was supreme. A warrior could hide in the ferns, wait for a Japanese soldier to pass, and deliver a single, fatal blow.

Similarly, the parang ilang proved its worth. The convex side of the parang ilang pushes the blade away from the cut, preventing it from binding in bone. This meant a warrior could strike and retrieve his weapon instantly—a necessary feature when fighting multiple opponents. The revival of headhunting in Borneo during WWII proved that these traditional weapons were not obsolete; they were perfectly evolved for their environment.

Modern Day Borneo: Echoes of the Past

Today, headhunting in Borneo is extinct as a practice. The spread of Christianity and Islam, along with modernization, has firmly ended the era of tribal warfare. However, the legacy remains visible and vital to tourism and cultural identity.

The Skulls in the Rafters

If you visit a traditional longhouse in Sarawak, particularly in the Skrang or Lemanak river areas, you may still look up to see a cluster of blackened skulls hanging in a rattan basket above the common corridor (ruai). These are the trophies of the past, preserved not out of bloodlust, but out of respect for history. They are a tangible connection to the era of headhunting in Borneo.

The residents will tell you stories of their grandfathers who fought alongside the Z Special Unit, or ancestors who wielded a mandau sword with supernatural speed. They are proud of their heritage—not the violence per se, but the bravery and the spirit of survival it represents.

Cultural Preservation

Museums across the island, such as the Sarawak Museum in Kuching or the Sabah Museum in Kota Kinabalu, house incredible collections. Here, behind glass, you can see the evolution of the parang ilang, the intricate carving of a mandau sword, and photographs of the Borneo headhunters from the colonial era.

For tourists from Australia, the connection is poignant. War memorials in Labuan and Sandakan honor the fallen, but the stories of the Z Special Unit and their Dayak allies offer a unique narrative of friendship born in blood.

Is it Safe to Visit?

A common question from Western travelers reading about headhunting in Borneo is, “Is it safe?” The answer is an emphatic yes. The Dayak people are renowned for their hospitality. The aggression once reserved for enemies has been replaced by a welcoming culture that treats guests like family.

When you enter a longhouse today, you won’t be greeted by a parang ilang drawn in anger, but by a glass of tuak and a warm smile. The topic of headhunting in Borneo is shared openly as folklore. You might even be invited to handle a dull, ceremonial mandau sword during a dance performance.

The Spiritual Legacy

While the physical act of headhunting in Borneo has stopped, the spiritual worldview that drove it persists in subtler ways. The Dayak people still hold deep respect for the spirit world. The concept of semengat (soul) is still relevant.

The festivals that once celebrated the return of a war party now celebrate the harvest or religious holidays, but the rhythm of the drums and the stomping of feet during the Ngajat (warrior dance) you can check on the Youtube video above, this dance evoke the adrenaline of the past. The dancer, holding a shield and a replica mandau sword, mimics the movements of stalking and striking, keeping the memory of the Borneo headhunters alive through art.

It is a reminder that headhunting in Borneo was not just about death; it was a high-stakes engagement with life, death, and the afterlife.

Conclusion: Respecting the History

The history of headhunting in Borneo is a tapestry woven with red threads of violence and gold threads of courage. For the outsider, it is easy to judge the past through the lens of the present. But to truly understand Borneo, one must look at the skulls not as symbols of horror, but as artifacts of a complex society that was trying to make sense of a harsh world.

From the silent rivers patrolled by Iban warriors to the jungle ambushes orchestrated by the Z Special Unit, the story is undeniable. The mandau sword and the parang ilang are no longer stained with blood, but they remain sharp reminders of a time when the spirit of a man was the most valuable currency in the jungle.

If you plan to visit, go with an open mind. Trek into the interior. Sit with the elders. And when you hear the phrase headhunting in Borneo, listen closely to the story that follows. It is the heartbeat of the island.

Ready to Explore the Wild?

If this history fascinates you, there is no better way to experience it than seeing it firsthand. Plan your trip to Sarawak or Sabah. Visit the Sarawak Cultural Village, hike the headhunters’ trail in Mulu National Park, or pay your respects at the Kundasang War Memorial. Borneo awaits—not for your head, but for your heart.

Explore the Foundations of Malaysia

To dive deeper into the events and figures that shaped our nation, this page connects to detailed guides and historical facts about Malaysia’s journey: